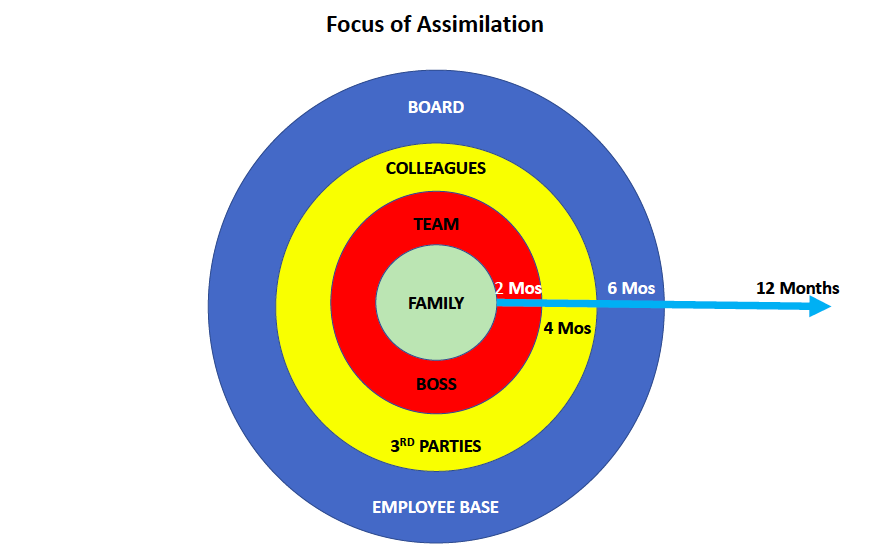

Taking a stab at a calendar for executive assimilation The first couple of months have three constituencies, your family, your team and your boss. Not to say these are complete after two months. Far from it! But this is when there is a lot of heavy lifting with these key groups. Getting things straight at home comes first, hopefully before you start the job. A position that creates turmoil for a spouse or children begins on a shaky foundation. You accepted the reassignment to Beijing without considering how your 5-year-old son will cope with his asthma? You might not be long for the job, and your company might not be too understanding about you reneging on your commitment. I was offered a position running my company’s business in Argentina. My wife and I checked it out over a Thanksgiving weekend and came away with the belief that the culture was a bad fit for our kids. I returned to the States to tell my boss, “No, thanks.” It was the right call for the family, even if it meant closing the door on opportunities within our international business unit. Within two months I had a new position in the North American business that I could commit to, without disrupting our family life. Having a series of conversations with your supervisor when you start is critical. Are your expectations of the job consistent with the reality you face? Can you set rules of the road in terms of communication and decision making? Often, we feel like we are expected to make an impact, when a boss still expects us to be learning. I think the real value of “quick wins” in the vernacular of Michael Watkins is, in part, to get the boss off your back temporarily, while you continue to learn. It’s probably more effective to have an open conversation with the boss about what how long they expect you might need to get up to speed before making decisions of consequence. I’ve spoken to successful CEOs or divisional presidents who made it clear that they were going to resist imposing their will on the organization until they felt like they had a sufficient understanding of the issues, the people, the processes, etc. Their first two months on the job entailed a crash course on the market, the organizational competencies, etc. And letting others make decisions was unnerving. Leaders make decisions. Not doing so is against their nature and contrary to what they think is expected of them. You cannot always get away with this strategy. Crises demand action, and leaders have to own that action. Sometimes there is no getting around it; you may have to act even in your ignorance. Management involves getting things done through other people. The people you will count on the most are the ones who report to you. So, the first 2 months involve getting to know them and having them become acquainted with you. A one-day facilitated session made popular by GE three decades ago is still state of the art. It addresses these questions:

Once your team is better acquainted with you, get to know them individually. How can they help you? What are their strengths? Who needs to be developed? What dynamics must you be sensitive to? Your reports will pay much more attention to you than you will to them. They are looking for little cues from you. When you say “we,” are you talking about this team, or your former employer? What evidence do they see of you delivering on commitments? How can they determine if you have their backs? How do you demonstrate adherence to cultural values? What won’t you tolerate? This is an ongoing process, and it changes as your team changes. But this begins to gel in the first two months. While you continue to work on relationships with family, boss and team, Months 3 and 4 add two other groups of constituents, colleagues and outside stakeholders. For the first couple months, you have met your colleagues, interacted with them and tried to mind your own business. As you feel more secure in the first ring of relationships, it’s time to get more involved in the interaction with your peers. This can be in the form of building alliances through reciprocation, asking questions and finding opportunities to move from professional to personal relationships. Be aware that your ignorance can be a point of leverage, allowing you to ask naïve questions without an agenda. At the same time, your ignorance has you at a decided disadvantage in organizational politics. If your peers feel you are oblique in a way that builds your own power base, don’t be surprised to get towel-snapped. With enough confidence in the critical internal relationships needed for success, many leaders begin to turn their attention outside of the organization. There may be vendors, strategic partners or customers that demand attention your attention. A sales leader whose success depends on direct relationships with customers can’t wait until Months 3-4 to focus on them. For most executives, this ring of assimilation recognizes that people who work for you own the primary 3rdparty relationships; forging external bonds comes after you make progress on the relationships with your own people. The next ripple out brings a focus on building links to board members and on the broader employee base beyond your own team. It’s important for the organization to know who a leader is and what their priorities are. Being public about your intentions will make it easier for your team to get traction. But your team deserves that your communications have credibility. Credibility requires you to be steeped in the business and the culture. And it’s not just your credibility at stake, but the credibility of all those whom you lead. An early pronouncement that shows your ignorance hurts those you must rely upon to succeed. Don’t dig a hole for them; be judicious about what you say and when you say it. In many businesses, board involvement is a quarterly affair. So, a C-suite leader’s first exposure to the full board may be sometime in the first ninety days. Your “rookie” label provides some insulation, assuming you avoid significant breaches in etiquette. Listen carefully, offer opinions or information when requested and don’t be afraid to admit to ignorance. The second board meeting, sometime between Months 4 and 6, is a different matter. If you don’t have information to answer a question, it is wise to address how you will get it. If a suggestion had been made in your first exposure to the board, prepare a report on actions you’ve taken. If you decide not to act on a board member’s request, communicate that to the individual board member before the next meeting takes place. If there is bad news to report, get it out, take responsibility and provide the planned remedy. Look for opportunities to interact with board members before the second meeting. Ask for their perspectives on issues you face or introductions to their connections who may provide value. Over Months 7-12, assimilation and relationship-building continue across all of these groups. You are able to manage greater complexity. Your familiarity with the system and with the people will allow you to assert yourself more. You can take more risks in challenging others, expanding your influence and making change happen. As you become more comfortable in the system, you can no longer use being new as a “get out of jail free” card. A year in, questions you ask are no longer viewed as naïve. Motives might be questioned. This is when the careful groundwork of your early assimilation will pay off. Peers, supervisors, direct reports and other stakeholders have had a chance to take your measure, to learn who you are and how you add value. You no longer are given the benefit of the doubt. Instead, you have earned your place.

1 Comment

|

AuthorExecutive Springboard President Steve Moss shares learning from years as an executive and a mentor. Archives

July 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed