|

For many of us, there are at least three steep climbs we make in our careers. They involve acquiring critical managerial and leadership skills, and they are often tied to specific titles or levels in a hierarchy.

1.Conquering scope and scale The first happens when we realize that time is no longer our friend. Early in careers and up through a Manager level, we are often individual contributors with a limited span of responsibility. The thoroughness of our work begins to get stressed as more responsibility is put on our plates. There comes a point when the requirements of the job are too great for one person to do in an exceptional job on everything. Responsibility and accountability begin to diverge. You may have ownership for results without being able to manage the task yourself. I remember having a very competent manager, Henry, working for me in a HQ marketing role. He had checked all the boxes and was eager for a more senior assignment. Henry assumed a Sr Manager position leading a nascent marketing organization of four people. It was his first time with direct reports, and he couldn’t let go of the work. He was uncertain of his team’s ability to do their work and he tried to do it all himself. Instead of diving in as he did before his promotion, he got stuck. The amount on his plate became paralyzing. It took Henry several months of coaching and training in prioritization and delegation before he got some traction. He finally internalized that, in his more senior position, parts of his former job were too low-value for him to continue doing, that he had to offload some work to do the more strategic job demanded of him. With that realization, he (reluctantly) delegated to his reports. With some oversight on his part, they succeeded and so did he. 2.Solving ambiguity with insight If there is a condition that defines director-level work, it may be working in ambiguous situations. You are asked to solve a problem, but nobody defines the problem for you. You see symptoms. You have lagging indicators. But the root cause has escaped people, until you are given the task. Let me share some 19th and 20th century wisdom here. Charles Kettering, head of research for General Motors for over a quarter century said, “A problem defined is a problem half solved.” The Prussian military analyst Carl von Clausewitz coined the phrase “the fog of war,” describing the lack of situational awareness that confronts participants in military action. He said, “A sensitive and discriminating judgment is called for; a skilled intelligence to scent out the truth.” Through all the confusion and lack of clarity, success comes from insight. Albert Einstein talked about how some people cut through the fog. “Creativity is seeing what others see and thinking what no one else ever thought.” Some undefined problems might be very difficult to uncover. Sometimes, people who viewed it before you just got caught in the fog. Whatever the case, seeing a problem for what it is and finding a solution is a milestone in a leader’s evolution. 3. Developing an enterprise orientation Executive Springboard mentor John Keppeler told me a story about when he had his first C-suite role. He led sales for CNS, the company that introduced Breathe Right nasal strips. The CEO, Marti Morfitt, gave him advice that rings true 25 years later. “John, you are a really good sales guy. Learn what it takes to be part of a cross-functional management team. Get out of your lane and be more than the VP of Sales.” Leadership teams are diminished by members who stay in their lanes, who protect their turf and who don’t challenge their colleagues to get better. Joe had all the functional skills that you would ever want from an Operations VP. Those who worked for him loved him. But his relationships with other members of the leadership team were another matter. Any suggestion about Operations was met with Joe's full-throated opposition. The only time he offered an opinion on another function was when it impacted his own. I can’t say he wasn’t a team player. It was just that he played on HIS team and not the company’s! It is critical that leaders develop a sense of working for the common good, not just supporting the interests of their team. There is a balance required. Your team needs you to be their champion and to provide them with political air cover. But successful organizations also demand more of their leaders, requiring them to operate with a wider lens.

2 Comments

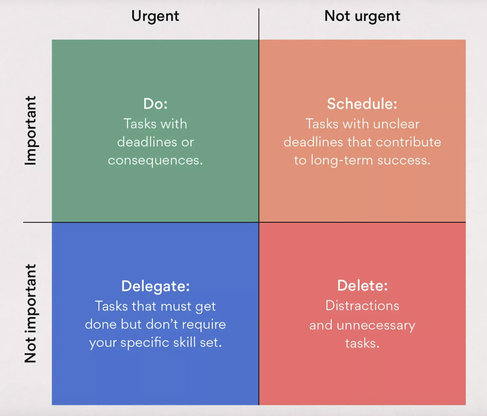

Congratulations! Your scope of responsibilities just expanded! An adjacent product line is now under your control, along with 3 additional direct reports and 50 people in total. Sorry, you don’t get a raise or a change in title. Just a portfolio to run with 20 less people than were working on this last week. That’s the reality faced by survivors of a downsizing. And it’s happening even in a time of robust national job growth. Despite over 900K jobs being added from January to March of 2024, employment is lumpy. SAP announced 8K layoffs in January. Dell and Microsoft cut 6K and 1900 respectively. Apple, IBM, Fisker and Bumble all have announced reductions. It’s hard to lose colleagues. We immediately mourn their loss. We worry about their future, though most of them will do just fine. Taking the extra step of offering to be a networking connection for them in their job search will pay dividends. As things sink in, we turn our attention to ourselves. LeadershipIQ’s survey of downsizing survivors shows that 74% say their own productivity has declined and that 87% are less likely to recommend their company as a great place to work. Sixty-one percent of remaining employees believe their company’s prospects are worse than before the downsizing. Survivor’s guilt is a real thing. The good thing is that it doesn’t last long. The bad thing is that it is replaced with the realization that you are doing more than one person’s old job. It's unlikely that anybody has figured out how you and your remaining colleagues will get the work done. It’s on you to figure this out and then to talk to your manager to get alignment. Don’t bring your manager the problem; give them your solution and get their buy-in. This is the time to use your prioritization and delegation skills. Consider the higher order responsibilities you’ve assumed. How much time will they take? What things of lesser importance need to go to somebody else, need to be checked on less frequently or can be eliminated entirely? Companies are notoriously bad at endings. Deciding to stop doing a task is an indication that it wasn’t important in the past, something that might be hard to admit. But your world has changed. Some things just are not as important as others. And there are few things more liberating than to stop doing a low-priority item. Now, think about the people who work for you. Some of your old responsibilities may cascade down to them. They should go through the same prioritization and delegation process as you, but they might not be as adept at it as you. This might be a good time to familiarize your reports with an Eisenhower matrix, as follows: Remember, it is likely that no task is completely unnecessary. But there are some things that are not mission critical that just might have to be deleted. As a manager, you can help those who report to you by keeping those items in “Delete” out of update discussions.

Your colleagues whose jobs were eliminated might get outplacement help. You are expected to navigate the issues you face without organizational help. If you have a coach, a mentor or a group you lean on for support, now is the time to reach out. Finally, create your own exit plan. Maybe your company will get it right, find a new level of efficiency and start on a new strategy of growth. Maybe you will find deep satisfaction in your new, broader responsibilities and see a path for career development. Maybe not. If your fears about the company’s and your own prospects persist, consider a new career opportunity while maintaining your current work. If you’ve been helping colleagues who were let go, they can reciprocate, having connected with companies that you’re likely to target. Reach out to headhunters to let them know you’re looking at options. Have your goals straight; a job search should focus on finding an opportunity outside of your current employer, not to leverage for better pay or a more senior title. Over half of managers who accept a counteroffer are gone within a year. When companies make workforce cuts, those left behind face trauma, guilt and uncertainty. They don’t get the equivalent help of an outplacement consultant, and they find themselves on their own to figure out a path through a newly laid minefield. Having a plan in place and a sounding board to confide in can be critical to your continued success. |

AuthorExecutive Springboard President Steve Moss shares learning from years as an executive and a mentor. Archives

July 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed