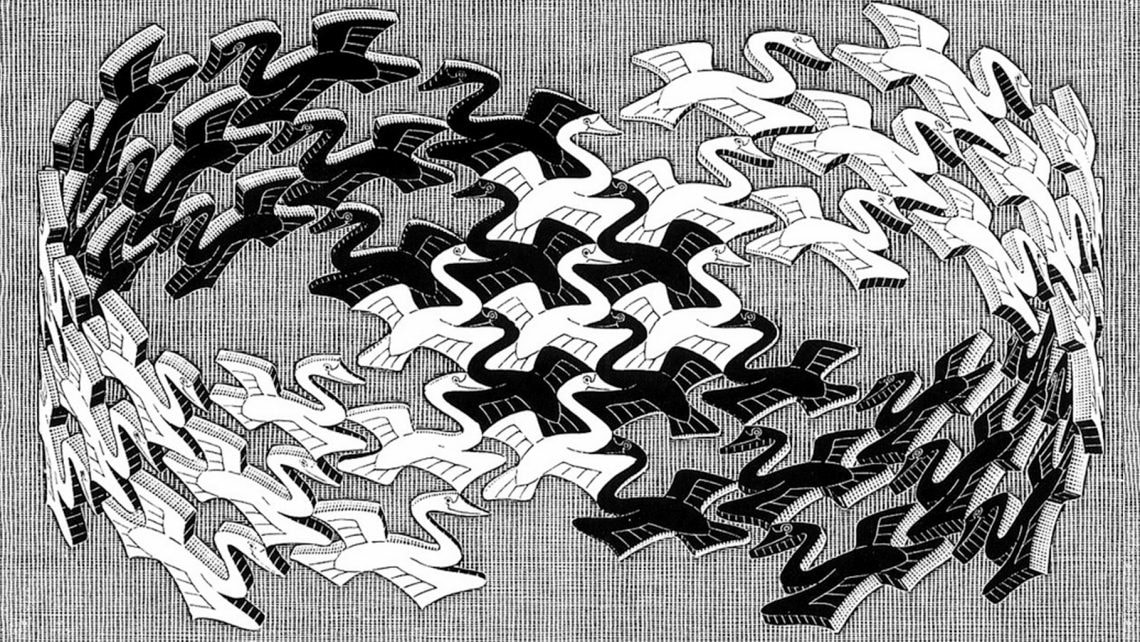

MC Escher, 1956, Swans I remember the morning my CEO made the announcement to the headquarters team that we were acquiring a competitor, but that the acquired company’s management would run the combined business. “Well,” he said, “We are all about to be made redundant.” That was not very accurate. His position (and mine) as part of the leadership team would be eliminated. Not so for the rank and file.

Thus began a bizarre 10-month period or retention bonuses, integration meetings and depositions with the FTC. All’s well that ends well. In this case, the combined business is still healthy today, despite the rocky start. (Maybe this is because our CEO was not involved in the integration!) That’s not how things usually go. Over 70% of mergers and acquisitions don’t attain the intended results. There are two broad areas that lead mergers to fail, numbers and people. First, the numbers... Careers are seldom furthered by telling a CEO that the acquisition they’re contemplating is a bad idea. M&A people sell deals internally. They are incentivized to do deals, not for the deals to prove successful. And there is seldom a consequence to overstating the synergies. After all, how often is the deal maker asked to become an operator in the Newco? So, the numbers are often biased towards unreasonable outcomes that lead towards unsatisfactory results after the businesses are integrated. Beyond a rosy bias on the benefits of an acquisition, there are numerous issues involving how employees react to mergers. Companies focus on the deal, not on integrating the team tasked with delivering the plan. Consider the following:

1. Get the M&A leader to own the results of the deal they propose. Give them significant responsibility in the new entity. When I was on the leadership team of the international division of a large food company, we had an acquisition in Australia and New Zealand. The lead dealmaker ran the combined business for a two-year period. The results after the acquisition were not stellar, until the head of sales succeeded the deal guy as President. But subsequent acquisitions had a very good track record, in part because the M&A group added a note of caution consistent with the possibility that they would be asked to run the target of their recommendation. 2. Get the CHRO involved during due diligence and beyond. They can conduct a culture assessment of the two organizations, understanding how work processes, communications preferences, folklore, decision-making and valued behaviors might align or clash and determining appropriate action. These are the parts of corporate culture that count more than whether jeans are allowed on Friday or what value statements say. The process of integrating culture requires an open look at what each organization does well, to understand what is needed for success and to involve the new leadership team of the merged entity. They can develop a communications plan. Communications need to start early and continue frequently, saying what is known and being transparent by fessing up to what remains unknown. Very early on, contingency communications should be developed, in case the deal is leaked. This would not address the specific deal, but it would be general about the company’s M&A strategies. It’s important to get ahead of gossip that can keep people from the important work that needs to get done. And, after the deal is announced, integration milestones should be provided with regular reports issued on how you do against them They can project the needs of the new organization and determine who, if anybody, in-house can address those needs. They can use an objective approach to determine who will be the leaders of the merged entity. This often involves reviewing the business objectives of the acquisition and identifying the competencies required to deliver them. They can determine who needs to be retained, what that might take and, as importantly, who needs to go quickly. They can assign an HR resource to the integration team and get their Learning & Development people involved. Having HR closely involved throughout integration keeps the process on track. Capabilities among the broad Newco leadership cohort can be built through a series of workshops, where priorities, metrics, expectations, decision rights and values are debated, and where trust-building exercises are enacted. And with people in new roles interacting with new colleagues, Newco leaders should have access to coaches or mentors to help them succeed. 3. Consider the brand before you close the deal. If you need to change the name of the acquired business, have you built that into the price? If you are leaving the acquired brand alone, how does that impact your legacy enterprise? I recently spoke to the owner of a marketing agency that has a niche in M&A branding. He told me that almost all of his clients come to him after the purchase is done. The acquiring company loads its balance sheet up with goodwill (the premium paid beyond the book value of assets for intangibles like brand), and it underestimates what it will take to keep the new brand on an even keel. A couple years later, the P&L takes a hit as goodwill impairment must be recognized. 4. Get beyond a winner/loser perspective. It only perpetuates unhealthy tribalism. Think of a merger as a marriage. Ideally, there is not a winner and a loser, just two parties that are better off together. Envision the end result of successful merger. There is only one team. When building that team, where do the best leaders come from? Is there anybody inside the organization who can handle the scale of the combined businesses, or do you have to go outside the combined employee base to find the right leader? 5. Build or buy integration expertise. Those organizations most adept at acquisitions use a playbook for integration that can be used from one deal to the next because they utilize an insight: the same issues tend to present themselves at the same time. A good way to get beyond tribalism is to bring in a merger integration specialist as an interim leader. Have them run a core integration team that is roughly balanced between the two entities. The integration leader is a neutral honest broker who is an expert in facilitating the merger process. This role might be even more important if you don’t do mergers often enough to have developed your own integration playbook. Maybe this resource resides in one of the merging businesses; maybe you need to invest in a consultant to play this role. We think that mergers result in cost reductions, as some people are viewed as redundant. We think that the personnel answers are currently residing in one of the two organizations about to be merged. These are bad assumptions. You might find that new positions are created, and there is nobody internally to fill them. Or that the scale of some responsibilities is too great for an incumbent. If current employees don’t fit the needs of the new organization, don’t be afraid to go outside. It is easy to get seduced by the promise of an acquisition, to concentrate on the potential for value creation and to gloss over the risk, especially the people issues that get in the way of success. But the risk is real, in your culture, in your dealmakers, and among the people who will live with the new reality. By providing the M&A team with consequences, getting HR involved in integration activities and focusing on the future organization rather than the legacy components, a merger has a much better chance of succeeding.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorExecutive Springboard President Steve Moss shares learning from years as an executive and a mentor. Archives

July 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed